Understanding energy security and why it is important today

Energy transition is a common word today, but such transitions never actually happened before in history. The word was first employed during the 1970s to avoid using the word energy crisis, perhaps more appropriate but more worrisome [1]. In times of energy crisis, available sources would become predominant and new sources could be added to the system, without replacing the other energies but rather producing even more to ensure energy security. By adding more potential energy sources into the system, countries were able to ensure supply with different resources when one was to be unavailable or too risky to use, while demand was rising. This is what happened for example when oil was developed in the United States at the end of the 19th century: because coal workers had too much influence over energy supply, the government chose to let oil become predominant over coal [1]. It is the same for the British Marine: because of the rivalry with Germany in the beginning of the 20th century, England chose to develop more oil powered boats. Although, Britain’s coal-powered marine was feared since the Opium Wars, rising competition in Europe led Churchill to choose oil over coal, and stay a step ahead thanks to higher energy density. Energy choices are not always possible however: after the fall of the USSR, Cuba was deprived of energy resources during the American embargo (1992). Because they couldn’t ensure energy security, they were forced to find economical ways to use it: carsharing, bicycle instead of cars, food rationing and organic fertilisers because pesticides were consuming too much energy, etc… The Cuban government also show interest in solar and biogas development, energies that they could produce on their own [1]. This is the kind of situation governments try to avoid at all costs by ensuring energy security: monitoring the electricity grid, extracting of resources adequately, maintaining good relationships with exporting countries…

To avoid situations where energy supply becomes too complicated, have thrived to make their energy system more resilient and conducted studies to understand the countries’ vulnerabilities [2]. Those vulnerabilities can be divided into 3 categories [3]:

- Sovereignty: related to geopolitics (import dependency, long term contracts for imports, fuels required, stability of exporting country…)

- Robustness: related to the status of resources and the energy system (energy transport and conversion efficiency, system capacity and reliability, oil refining efficiency…)

- Resilience: related to the system ability to respond to different impulses (demand per sector and person, value added to the initial resource, total final energy consumption by sector…)

Energy security was also the main reason why the European Steel & Coal Community (former EU) was created after the 2nd World War [4], in a context where energy exchanges were becoming important between European countries, to avoid disruptions of exchanges due to tensions and control competition. Today, these initiatives have contributed to strengthen the European inside energy market : rapid exchanges are possible thanks to the free movement of people and goods. However, the outside market is not as reliable. Indeed, European countries need to buy more than half of their energy from outside of the EU to support their needs, from the Middle East or countries like Russia. Based on this article by [4], the higher risks for external supply in the EU are related to gas, then oil, and finally coal. And as world gas consumption is likely to increase while gas production inside the EU isn’t, supply risks will become even more important.

For most countries on the global scale however, the biggest supply risks are related to oil. Production and consumption regions are also very distinct: countries in Africa, the Middle East or the former Soviet Union produce but don’t consume a lot, while Europe, North America and East Asia are important consumers. Dependence risks in oil importing countries are usually related to supply, environment or market (price fluctuations). These risks vary between countries: developed countries like Japan or Switzerland are more susceptible to supply risks whereas developing countries like India are more susceptible to market risks. Indeed, policies aimed at fixing market risks are more effective because they can be managed inside the country so many developed countries have already good market tools to prevent the market risks, whereas supply risks are harder to deal with [5]. The best methods to prevent these risks today are to diversify energy imports (different suppliers, different fuels), to improve oil efficiency or to create groups of consuming countries to decide on the common attitude towards groups of exporting countries like the OPEC.

To ensure energy security, it is important to understand the main characteristics of energy systems [6]:

- Vertical complexity: energy flows in the system from the producer to the consumer via different actors

- Horizontal complexity: energy and energy resources are exchanged between actors. Actors also interact with their surroundings.

- Entailed costs: energy systems have a cost: production, consumption, transmission and externalities need to be addressed. Because energy is directly related to growth, a big part of the economy must be focussed on these costs.

- Path dependency and inertia: energies that are used for a long time in the system are hard to upgrade or replace, this inertia is even more important as the system gets more complex.

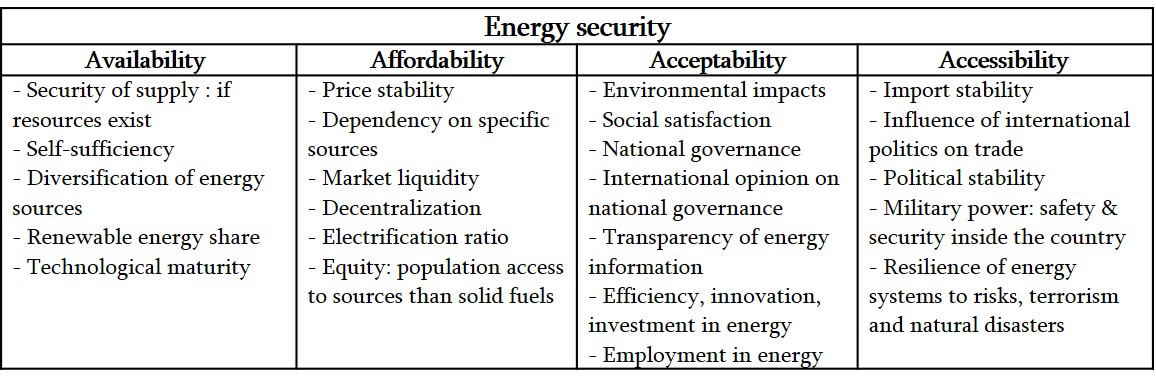

Studies have been conducted to group factors for energy security in separate dimensions. Based on this article by Jinghzeng R. and Benjamin K.S. [7], energy security can be managed considering 4 dimensions: availability (of resources and systems, self-sufficiency), affordability (cost of resources, system, and market status), acceptability (social opinion on energy governance and policies, adequate investments, employment, environment protection) and accessibility (geopolitical status, trade stability, resilience of energy systems to crisis). These dimensions interact with each other: for example, availability has an important influence on affordability and acceptability because if a fuel is easily available then its price can be lowered, and it can be socially acknowledged as a reasonable resource. Affordability also has an important influence on acceptability and accessibility because maintaining control on the cost of resources, upgrading the energy system, promoting decentralization and the use of electricity increases social satisfaction, enhances the energy system and strengthens governance [7]. Among those dimensions, availability is the main cause of energy security: measures need to be implemented because energy resources are not always available in the first place. On the contrary, affordability, acceptability and accessibility are effects of energy security: energy security policies affect geopolitics, social opinion, and the economy. Consequently, availability should be considered as the most important dimension of energy security [7].

Because energy is essential for economic growth, to stay competitive in our current world and maintain a good quality of life, energy security will become even more important in the future. As energy resources are becoming more precious, it is important to understand how national and international systems work to anticipate and avoid energy crisis like in Cuba during the embargo. Finally, to improve resource availability, developing renewable energy is a good strategy: it will encourage the diversification of energy sources and offer more options to manage the energy supply in the system.

Sources:

[1] Jean-Baptiste F. (2014, June 6th). Pour une histoire désorientée de l’énergie. HAL.

https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00956441/

[2] James G., Alessandro C., Brian Ó G. (2016, December 22nd). Energy security assessment methods: Quantifying the security co-benefits of decarbonising the Irish Energy System. Energy strategy reviews.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X16300621

[3] Aleh C., Jessica J., Vadim V., Nico B., Enrica De C. (2013, November 13th). Global energy security under different climate policies, GDP growth rates and fossil resources availabilities. Climatic Change.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-013-0950-x

[4] Chloé L.C., Elena P. (2009, July 9th). Measuring the security of external supply in the European Union. Energy Policy.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421509004091#tblfn2a

[5] Eshita G. (2008, January 15th). Oil vulnerability index of oil-importing countries. Energy Policy.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421507005022

[6] Andreas G., Benjamin K.S. (2011, November 17th). The uniqueness of the energy security, energy justice, and governance problem. Energy Policy.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421511008263

[7] Jinghzeng R., Benjamin K.S. (2014, September 22nd). Quantifying, measuring, and strategizing energy security: Determining the most meaningful dimensions and metrics. Energy.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360544214010482